Flowers of Evil and the Macabre Literary Imagination of Symbolism

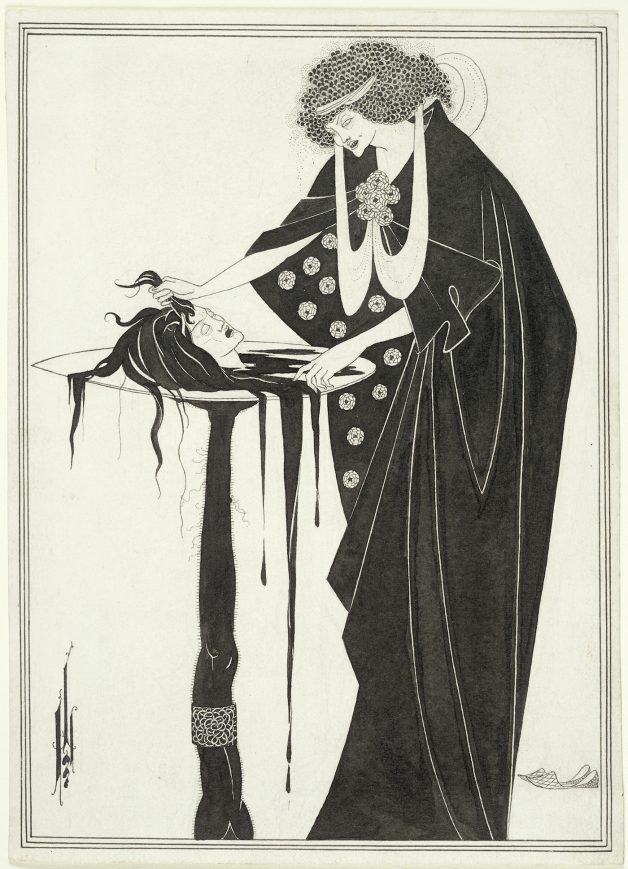

Vampires, fountains of blood, giantesses, dancing serpents, and “casks of hatred” populate Charles Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du Mal, a collection of poems from 1857. Similarly nightmarish imagery fills Flowers of Evil: Symbolist Drawings, 1870–1910, on view the Harvard Art Museum. Named after Baudelaire’s collection, the exhibit presents nearly 40 works by artists affiliated with symbolism, a 19th-century cultural force that bridged Impressionism with 20th-century movements.

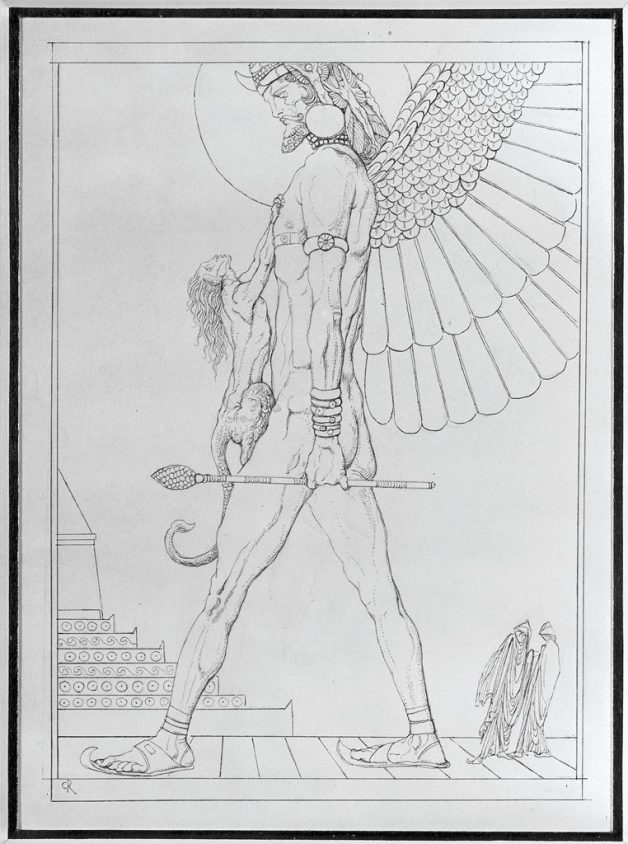

Symbolist artists — including Aubrey Beardsley, Jean Delville, and Odilon Redon — were united less by style than by their shared intention of illustrating invisible aspects of human experience. Like psychologists of the period, including Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung, Symbolist artists were concerned with dreams, visions, spirituality, mythology, archetypes, and other mysterious functions of the unconscious mind. “In Symbolism fact and world become mere pretexts for ideas; they are handled as appearances, ceaselessly variable, and ultimately manifest themselves only as the dreams of our brains,” wrote Belgian poet Emile Vergaeren. To visualize this subjective character of experience, figures in these drawings appear gauzy and translucent; objects look not quite solid. Landscapes shimmer, cast in what Baudelaire called “misty shrouds.”

“Man passes … through forests of symbols,” Baudelaire wrote in “Correspondences,” a poem considered the touchstone of the Symbolist literary movement. Baudelaire owed much of his macabre aesthetic to Edgar Allen Poe, whose works he translated into French. (Symbolism was centered in France, but also reached Austria, Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, England, and the United States.) Symbolist visual art, in turn, wouldn’t have existed without the influence of Poe, Baudelaire, and other writers. The “forests of symbols” in these drawings are best understood in context of the literature that inspired them: Many were originally created as book or magazine illustrations; others are dark, modern spins on classic tales and Biblical scenes, stripped of their usual piety…

See Full Article below @ HYPERALLERGIC

Flowers of Evil and the Macabre Literary Imagination of Symbolism

May 21, 2016–August 14, 2016

University Teaching Gallery, Harvard Art Museums

Below is the Museums Exhibition Blurb

The exhibition explores the mysterious visual world of symbolism, an open-ended cultural phenomenon of the late 19th century that formed an important bridge between impressionism and modernism. Yet more than these two movements, symbolism sought to evoke ideas subjectively—through color, form, and composition—rather than objectively representing worldly appearances. The title of the show is inspired by Les Fleurs du Mal (1857), an influential collection of poems by Charles Baudelaire, thus alluding to the literary antecedents of the movement.

Symbolist drawings were not united by a single technique or style, but by the artists’ shared desire to make the invisible visible—whether they chose subject, form, or some combination of the two as their major aesthetic focus. Often enigmatic, these graphic works served as signs of a deeper or higher degree of consciousness, beyond the literal objects that they depicted. Symbolism enabled artists to confront an increasingly uncertain and complex world, one that they alternately viewed in terms of degeneration and decadence, idealism and reform.

Featuring 40 drawings, mainly from the permanent collections of the Harvard Art Museums, this exhibition covers some of the major themes of symbolism, such as dreams and visions, spirituality, nature, and the relationship between society and the self. It offers an expansive view, including not only artists who identified themselves as symbolists but also influential precursors, as well as artists active at the end of the movement. The exhibition acknowledges the international nature of symbolism, which was centered in France but extended to countries such as Austria, Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, England, and the United States.

Curated by Edouard Kopp, the Maida and George Abrams Associate Curator of Drawings at the Harvard Art Museums.

The exhibition is made possible in part by funding from the Melvin R. Seiden and Janine Luke Fund for Publications and Exhibitions and the José Soriano Fund.

Share your experience on social media: #DrawingsatHarvard