Liber Libræ sub figurâ XXX – The Book of the Balance:

“15. Nevertheless have the greatest self-respect, and to that end sin not against thyself. The sin which is unpardonable is knowingly and wilfully to reject truth, to fear knowledge lest that knowledge pander not to thy prejudices.

“16. To obtain Magical Power, learn to control thought; admit only those ideas that are in harmony with the end desired, and not every stray and contradictory Idea that presents itself.

“17. Fixed thought is a means to an end. Therefore pay attention to the power of silent thought and meditation. The material act is but the outward expression of thy thought, and therefore hath it been said that ‘the thought of foolishness is sin.’ Thought is the commencement of action, and if a chance thought can produce much effect, what cannot fixed thought do?”

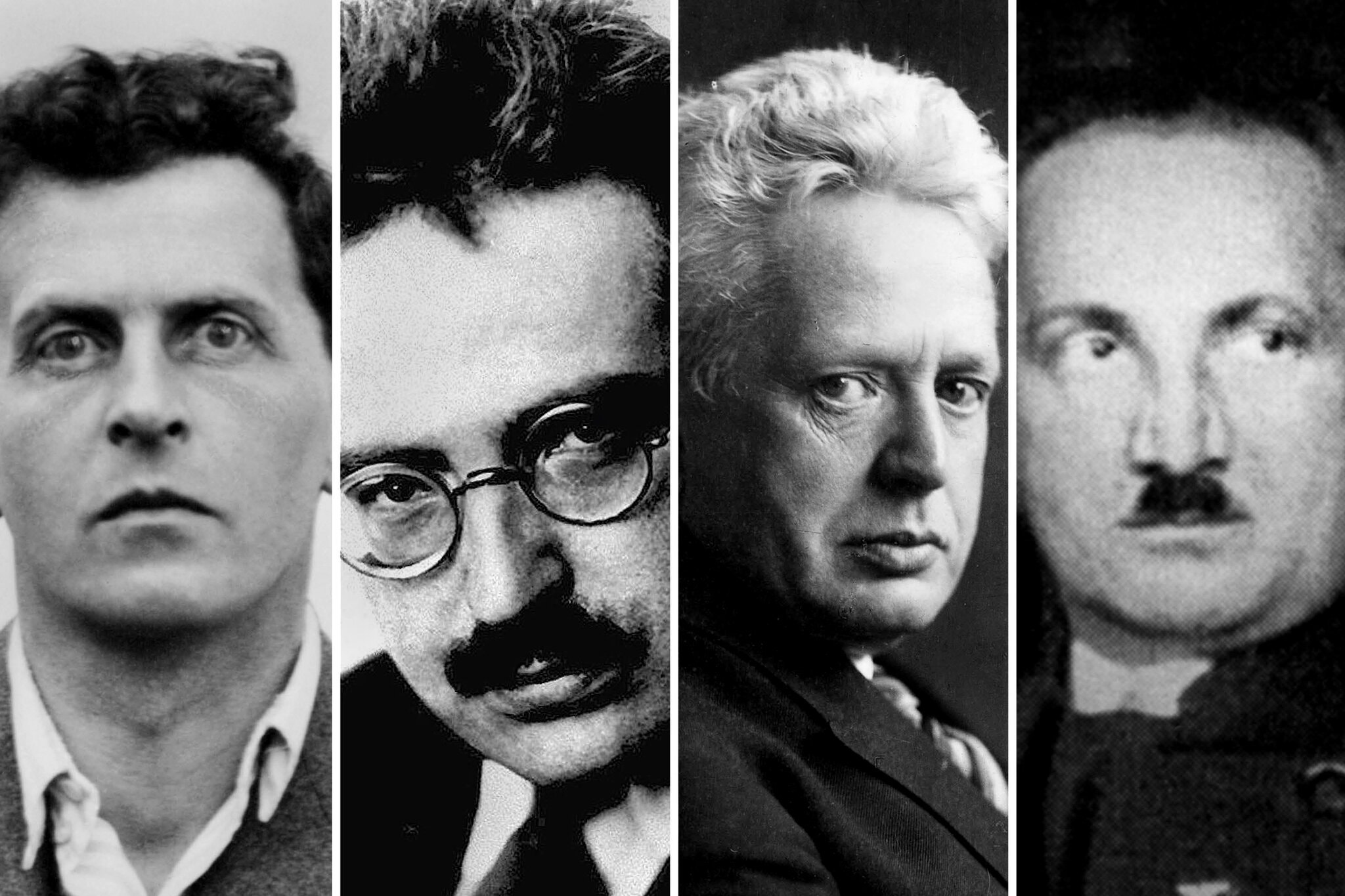

At the end of this passed Summer, the New York Times Book Review ran a, err, book review of Time Of The Magicians, regarding certain key figures dealing in such matters in the early 20th century. These would NOT include Aleister Crowley, MacGregor Mathers and Franz Bardon – Wolfram Eilenberger’s book examines the careers of the European philosophers Martin Heidegger, Ernst Cassirer, Walter Benjamin and Ludwig Wittgenstein. And why should modern occultists care? Eilenberger suggests, without hard-selling the notion, that these philosophers posited that human beings could take control and alter their own thought processes and views of manifest reality and thereby their experience of and interactions with their perceived environment. I’d suggest that this is not substantially different than what Aleister Crowley prescribed as the means of performing effective magick. A few excerpts from the review state:

“Eilenberger explains that philosophers in 1920 faced a common task: to ‘draw up a plan for one’s own life and generation, which moves beyond the determining ‘’structure’’ of ‘‘fate and character’’ … to break away from the old frameworks (family, religion, nation, capitalism) … finding a model of existence that made it possible to process the intensity of the experience of war, transferring it to the realm of thought and everyday existence.’…

“In 1919, as Eilenberger recounts, Martin Heidegger delivered his first lecture at the University of Freiburg to ‘a scattered crowd of mostly defeated men … who now had to pretend that they saw themselves as having a future.’ This crowd of returning soldiers was downtrodden and vulnerable, which is to say highly susceptible to influence. These men had no future — no money, no job, no pride, no hope — but, according to Heidegger, they maintained the most basic, but also most vital, philosophical choice. He implored his soldiers-turned-students to exercise it: to ‘learn thinking anew’ and, in so doing, to ‘leap’ into ‘another world.’

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/04/books/review/time-of-the-magicians-wolfram-eilenberger.html.