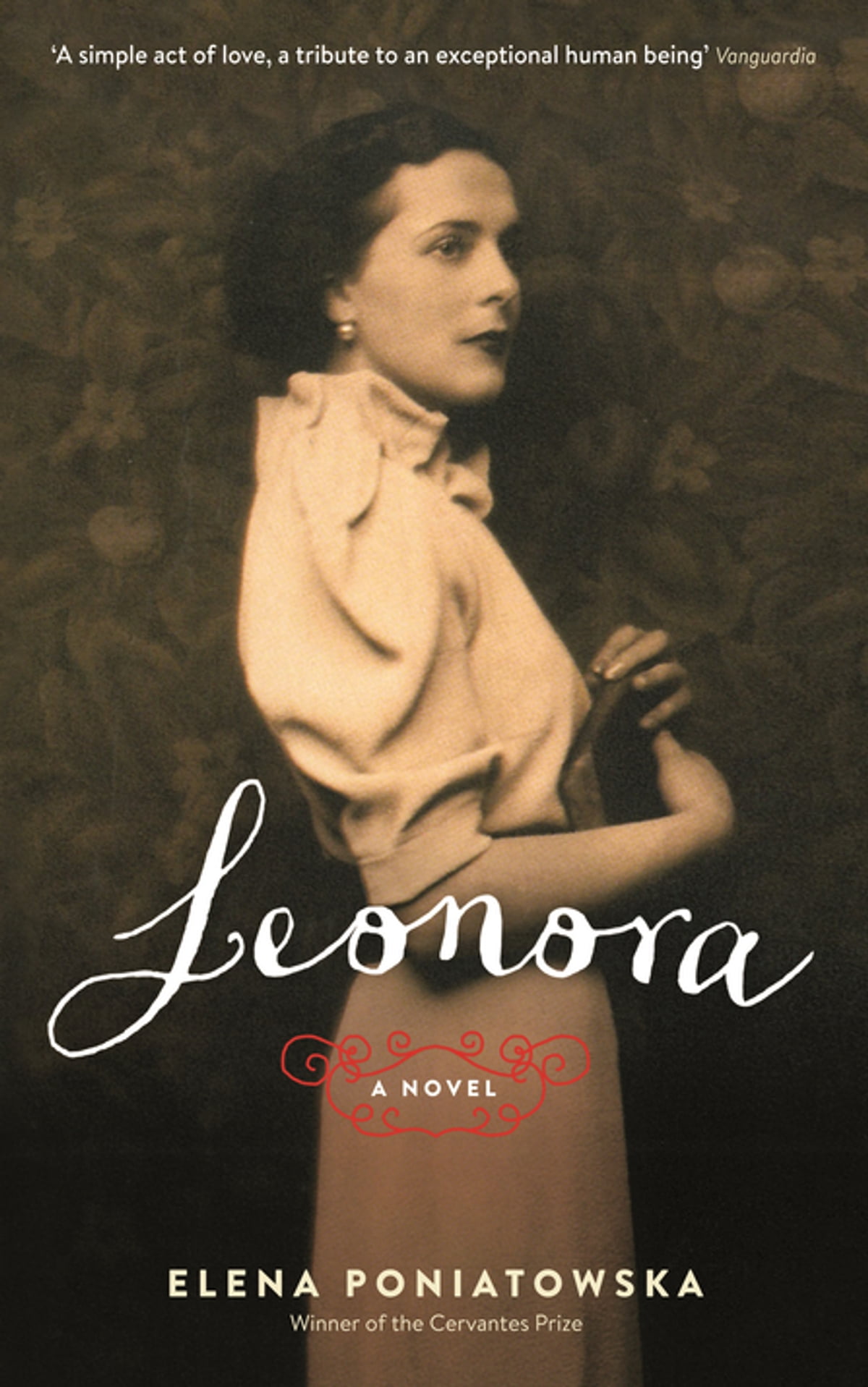

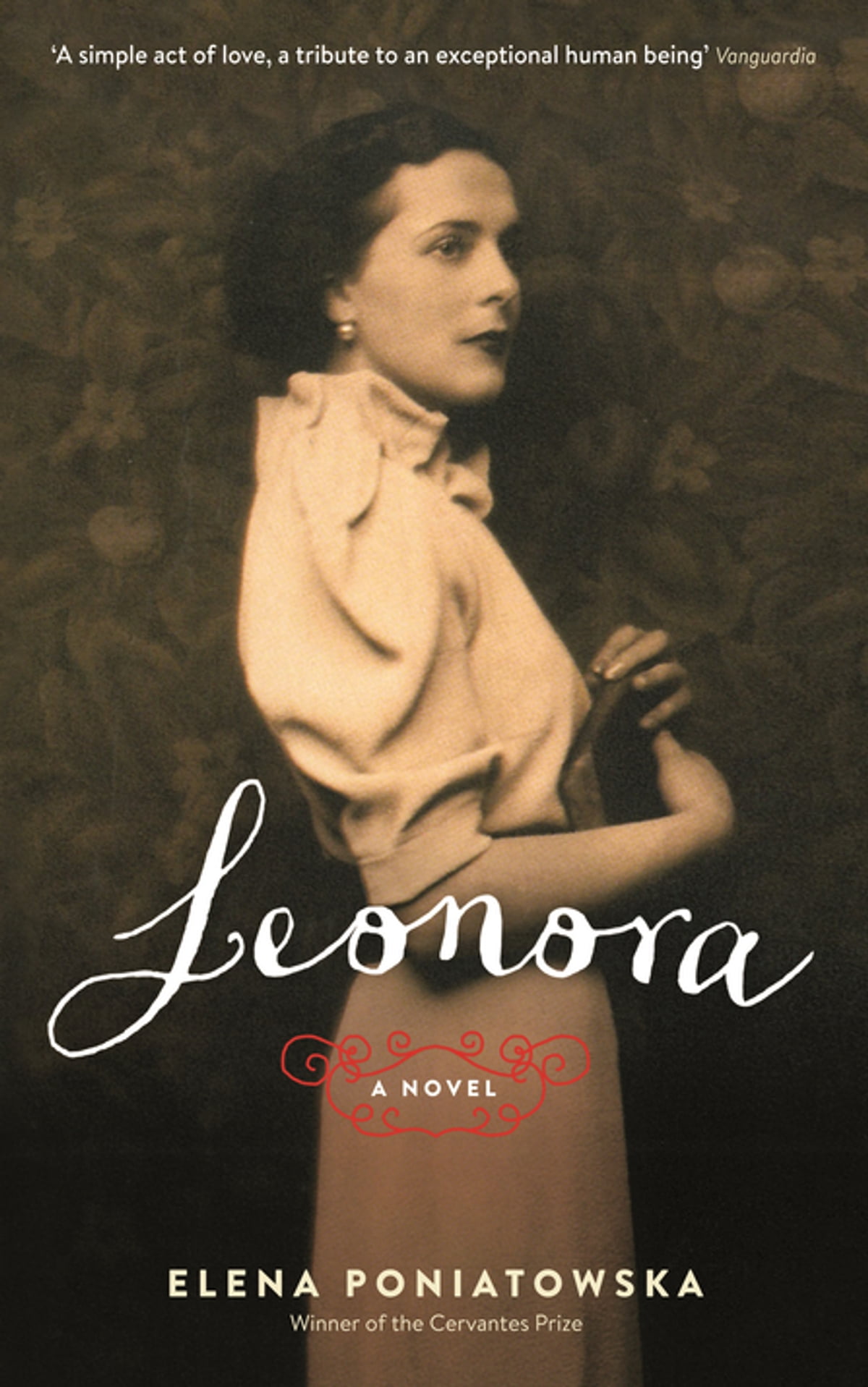

Fascinating news about a new book about the surrealist artist, author and sorceress Leonora Carriginton from the https://www.facebook.com/leonoracarringtonweisz FB page:

Leonora by Elena Poniatowska

First of all, Leonora is a novel. It’s neither a review of Leonora Carrington’s painting, nor a biography. It’s a work based on conversations we had during multiple interviews, on books by Leonora herself and those that have been written about her: Whitney Chadwick, Susan L. Alberth by Julotte Roche.

I met Leonora Carrington in the fifties. The first interview I did appeared in the newspaper Novedades, which no longer exists.

Over the years, his home on Chihuahua Street in the Rome Colony became the cave of spells, a powerhouse, a magnet stone. Leonora’s tea, a love filter, a come back to life. I also treated her in the gallery of Ines Amor on Milan Street, in the Antonio Zouza Gallery, (first on Genoa Street, above the Konditori, then on the corner of Paseo de la Reforma and Berna Street). I ate with her around Elena Urrutia’s table, at Isaac Masri’s, at Natalia Zacharias’ table, which is a charm. I continued to see her with Maria Felix, with the English Nancy Oaks, in the company of the painter Eliana Menassé and in book presentations alongside Merry MacMasters, as well as in the various tributes paid to her in universities and cultural auditoriums. She always had a smile for me and that was a reason for happiness so following her was a privilege. I keep in my heart the image of the last time you smiled at me on the staircase of the Mining Palace.

Even more than Leonora, I treated photographer Kati Horna, who knew how to love everyone. Our office brought us together. We were both journalists and on many occasions we took the same bus. When she took her daughter Nora to ballet classes in Coyoacán, I accompanied Paula, my daughter, to be scolded by teacher Ana Castillo because some loops escaped from the mandatory net. The two mothers chatted while waiting together. We were bonded by the same feelings.

I met Chiki at several meetings where he was doing his work as a photographer. It was very easy to recognize him by his Basque hat and shyness. He always stood back and waited with great dignity for the other reporters to finish.

Leonora is an approach to what could be an exhaustive Leonora Carrington biography. If I could write it, I would gladly, although this novel may stimulate others to talk about it and become a source of information. In Leonora, there are still countless varieties to discover.

I have visited Leonora often over the past few years. Talking to her about her childhood was easy. I told him mine and, despite the fifteen year age difference, there were many similarities in the European way we were brought up. Between things and between roses there are wonderful similarities. Now I realize that Leonora’s background looks like those of the protagonist of La Flor de Lis. From her childhood, Leonora spoke with ease; of Cardiazol in the doctor Mariano Morales’ clinic in Santander, with true anguish. He seemed to be denouncing the application of this seizure-producing drug that goes far beyond the amour fou that André Breton preached. By telling me, he was looking for my outrage and solidarity. I sure would have them! but how? Had three shots of Cardiazol, eyes wide open. What he didn’t talk about was Max Ernst’s. When I asked him if it had been his great love, he replied that every love was different; when I told him that his marriage to Renato Leduc had been just convenience, he replied: Well, neither.

I also interviewed Gaby and Pablo, guardians of the drawbridge that leads to her mother. I gave you chapters to read from Leonora. The two sons patiently take the worship of their mother and I’m sure that sometimes that devotion is a weight they carry like a tombstone on their shoulders. Plus they have their own life, their family, their job. They watch over her day and night.

Poniatowska and Carrington maintain a 60+ year friendship. Here at the Poet House in 2005Photo Roberto Garcia Ortiz. The door leading to Leonora is narrow. Few are the chosen Leonora sometimes regrets her loneliness but refuses to come out of it. I proposed to her to go see trees in the Desert of Lions, she replied: I will pass; on another occasion, I wanted to get her excited about the movie Young Victoria, but she did not encourage either and, when I talked to her about the possibility of receiving a visitor, she replied: Yes, but not any visitor. Leonora no longer tolerates interviews. The only thing he accepts is to go to eat, sometimes, to Sanborn’s close to Plaza Miravalle, where the horses of the Cibeles play. There, the waitresses know her, they know which table she prefers and before she asks for the menu they have already brought her invariable eggs to the Mexican and not even finished the few refried beans that accompany the dish.

He has also agreed to eat at my home accompanied by Gaby Weisz, his son, and Pati, his daughter-in-law. For me those were save days.

Yolanda Gudiño, her caretaker, is a gem. He loves Leonora, admires her, protects her. Accompanied by Yeti, the dog gifted by Doctor Isaac Masri. The two most spoken names in that Chihuahua street house are Yolanda and Yeti.

Gaby assured me that her grandmother’s name was Mairie and stamped with her fist and wrote Maurie’s name in one of the chapters, however Joanna Moorhead, Leonora’s niece who frequently comes from England to visit her, assured me that the name was Maurie and that even so it was written on his grave.

Everything that appears in this play had already been written in the tales of Leonora, in her novel The Acoustic trumpet, in her theatrical pieces, in the interviews she has granted. Both Whitney Chadwick and Susan L. Alberth, whom I had the privilege of meeting at Casa del Poeta in Mexico, is an art critic, experts in surrealism and extraordinary biographies. I remember Georgiana Colville’s enthusiasm for surreal women. The publishing house ERA published in Mexico the endearing book by Julotte Roche, who interviewed the inhabitants of St. Martin D’Ardeche for her Max and Leonora. Henri Parisot was a translator and disseminator of Leonora’s literary work in France. Agustín Bartra translated it in Mexico. Her fan list is very long, but I feel especially marked by Rosemary Sullivan’s book Villa Air Bel, which while not so much to do with Leonora, is all about the spirit of the time.

What had not been written before is the relationship between Leonora and Renato Leduc, the ironic, accurate and playful poet who brought her to Mexico. While writing the novel, I was lucky enough that Patricia Leduc, Renato’s daughter, gave me a couple of unpublished photographs that her father had taken of Leonora, as well as a beautiful letter that the painter wrote to him and that appears translated in the novel.

The help I received from Sonia Peña and Mayra Perez Sandi Cuen was invaluable, as well as that of Rubén Henriquez, who let himself be so caught up in history that he knows by heart how each paragraph starts and ends.

Leonora is not only an act of love but also a tribute to the life and work of this woman who has enchanted Mexico with her colors, her words, her delusions, her starts, her stories. He brought to our country all the memories of their past lives, all the landscapes, the roads under acacia, all the vegetables that Mexico didn’t eat like salsifis, endivias, artichokes. He brought Simone Martini, Piero della Francesca, Bosco and Grünewald. He could have lived in England, his country of origin, in the United States, France or Spain, but it is a privilege to know that an artist of his height has decided to be Mexican. The debt to her is priceless.