In the profane world, Jimmy Page is, most likely, the standard bearer of Thelema thanks to the lasting popularity of the group he created, Led Zeppelin. One might suggest though that this has been a disservice to this curious mix of modernist ethics, admittedly conceptualized pantheon and poetically rendered vision of the interaction between scientific data and spiritual experience.

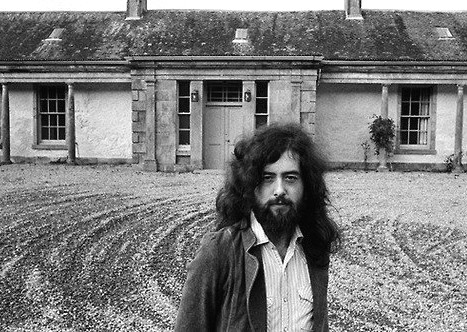

As the trope goes, a central tenet is the Goddess Nuit’s pronouncement “Do what thou wilt, shall be the whole of the Law. Many Thelemites I’m familiar with accept one of Crowley’s explanations that this means 1) determine the purpose for which you, as a discarnate soul, chose to incarnate 2) free yourself of all influences outside of yourself so that you can pursue that purpose and no other (which doesn’t have to mean denying outside input – just not being unthinkingly controlled by them… perhaps). Based on the multitude of public accounts of his life, Page appears to have seen this Golden Rule as permission to indulge in every passing whim and caprice – sexual exploitation of underage females (14 year old Lori Mattix for instance), cocaine and heroin addiction, recreational violence. And yet… he did open and support an exemplary bookstore making occult texts readily available in London, bought Crowley’s one-time estate, Boleskine House, and was seeking to create deluxe editions of out-of-print Crowley texts… I dunno – did he actually read many of them? Deeply? Repeatedly? Who knows.

Accordingly, a recent New Yorker review of Led Zeppelin: The Biography by Bob Spitz, the latest in a long queue of books on the chequered history of Led Zeppelin’s characterizes our noble Creed thusly:

“That’s the good satanism. What about the actual diabolical activity—the violence, the rape, the pillage, the sheer wastage of lives? Jimmy Page was a devoted follower of the satanic “magick” of Aleister Crowley, whose Sadean permissions can be reduced to one decree: ‘There is no law beyond do what thou wilt.’ If the predetermined task of rock gods and goddesses is to sacrifice themselves on the Dionysian altar of excess so that gentle teen-agers the world over don’t have to do it themselves—which seems to be the basic rock-and-roll contract—then the lives of these deities are never exactly wasted, especially when they are foreshortened. Their atrocious human deeds are, to paraphrase a famous fictional atheist, the manure for our future harmony. In the nineteen-sixties and seventies, they died young (or otherwise ruined their health), so that we could persist in the fantasy that there’s nothing worse than growing old.”

OUCH!

Otherwise, the review’s pretty cool and a nice quickie overview of many of the elements of the group’s story that aren’t part of the most popular narratives (though I wasn’t amused by the denigration of the late Richard Cole who I knew to be a quite sweet bloke, RIP).