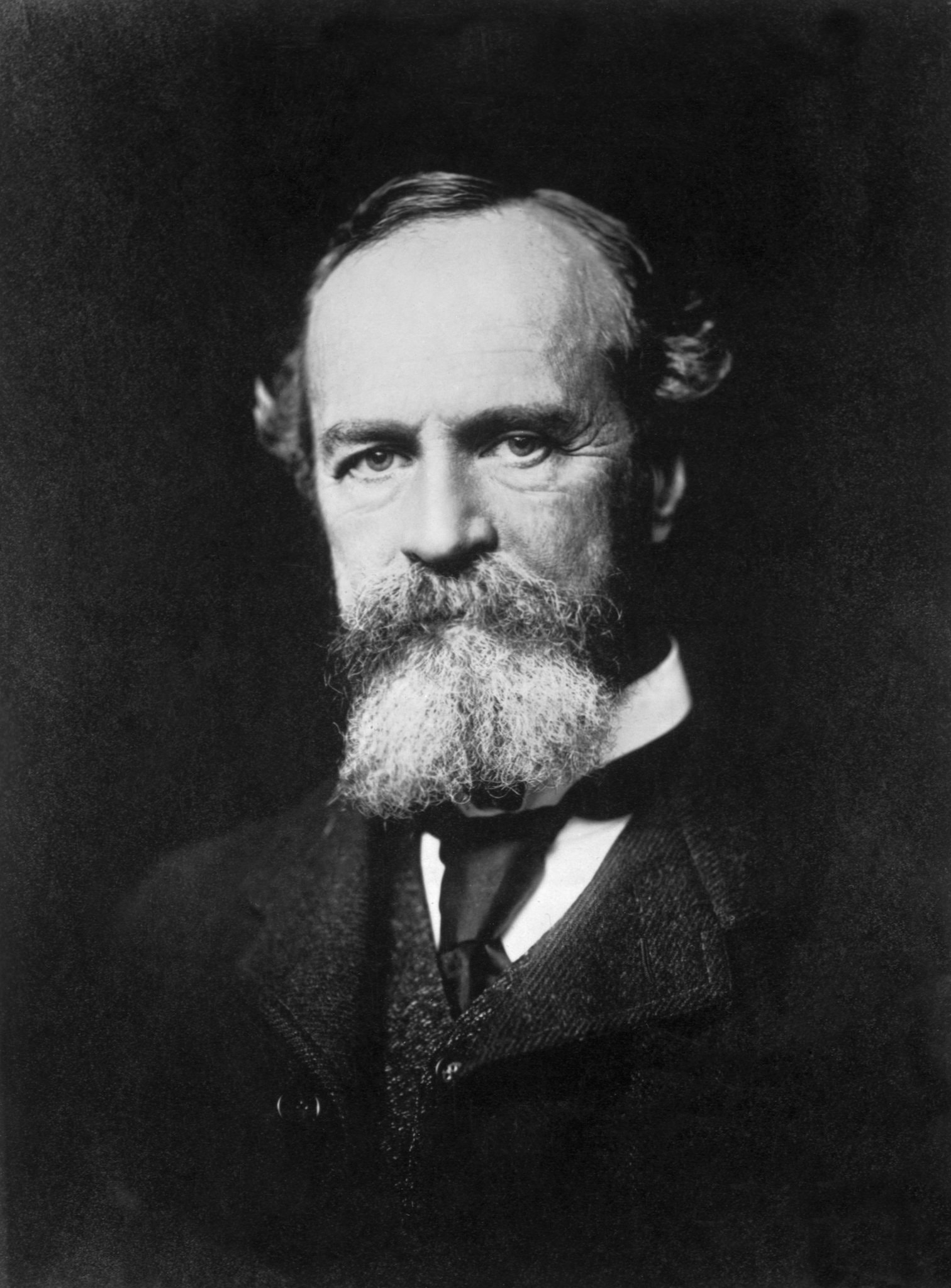

I was reading a review of SICK SOULS, HEALTHY MINDS: How William James Can Save Your Life, a new book by John Kaag about the psychologist/philosopher William James – Brother of noted writer Henry James. A segment of the review struck me as perhaps pertinent to the experiences many of us are having at the moment:

“James stared down ‘the prospect of persistent existential disillusionment,’ though the warm tone of his work belies this description, and often framed experience in a Buddhist-like perspective: ‘If one looks carefully,’ as Kaag puts it, ‘suffering is not the exception but the rule.’ Can we actively reduce this suffering? James thought so, or that at least it would truly benefit us to act as if we could. ‘My first act of free will,’ he wrote, ‘shall be to believe in free will.’

Meanwhile, here’s the BBC’s account of the Buddhist approach to suffering:

The First Noble Truth

Suffering (Dukkha)

Suffering comes in many forms. Three obvious kinds of suffering correspond to the first three sights the Buddha saw on his first journey outside his palace: old age, sickness and death.

But according to the Buddha, the problem of suffering goes much deeper. Life is not ideal: it frequently fails to live up to our expectations.

Human beings are subject to desires and cravings, but even when we are able to satisfy these desires, the satisfaction is only temporary. Pleasure does not last; or if it does, it becomes monotonous.

Even when we are not suffering from outward causes like illness or bereavement, we are unfulfilled, unsatisfied. This is the truth of suffering.

Some people who encounter this teaching may find it pessimistic. Buddhists find it neither optimistic nor pessimistic, but realistic. Fortunately the Buddha’s teachings do not end with suffering; rather, they go on to tell us what we can do about it and how to end it.

The Second Noble Truth

Origin of suffering (Samudāya)

Our day-to-day troubles may seem to have easily identifiable causes: thirst, pain from an injury, sadness from the loss of a loved one. In the second of his Noble Truths, though, the Buddha claimed to have found the cause of all suffering – and it is much more deeply rooted than our immediate worries.

The Buddha taught that the root of all suffering is desire, tanhā. This comes in three forms, which he described as the Three Roots of Evil, or the Three Fires, or the Three Poisons.

The Three Fires of hate, greed and ignorance, shown in a circle, each reinforcing the others. Photo: Falk Kienas ©

The three roots of evil

These are the three ultimate causes of suffering:

- Greed and desire, represented in art by a rooster

- Ignorance or delusion, represented by a pig

- Hatred and destructive urges, represented by a snake

Language note: Tanhā is a term in Pali, the language of the Buddhist scriptures, that specifically means craving or misplaced desire. Buddhists recognise that there can be positive desires, such as desire for enlightenment and good wishes for others. A neutral term for such desires is chanda.

Cessation of suffering (Nirodha)

The Buddha taught that the way to extinguish desire, which causes suffering, is to liberate oneself from attachment.

This is the third Noble Truth – the possibility of liberation.

The Buddha was a living example that this is possible in a human lifetime.

Nirvana

Nirvana means extinguishing. Attaining nirvana – reaching enlightenment – means extinguishing the three fires of greed, delusion and hatred.

Someone who reaches nirvana does not immediately disappear to a heavenly realm. Nirvana is better understood as a state of mind that humans can reach. It is a state of profound spiritual joy, without negative emotions and fears.

Someone who has attained enlightenment is filled with compassion for all living things.

After death an enlightened person is liberated from the cycle of rebirth, but Buddhism gives no definite answers as to what happens next.

The Buddha discouraged his followers from asking too many questions about nirvana. He wanted them to concentrate on the task at hand, which was freeing themselves from the cycle of suffering. Asking questions is like quibbling with the doctor who is trying to save your life.

The Fourth Noble Truth

Path to the cessation of suffering (Magga)

The final Noble Truth is the Buddha’s prescription for the end of suffering. This is a set of principles called the Eightfold Path.

The Eightfold Path is also called the Middle Way: it avoids both indulgence and severe asceticism, neither of which the Buddha had found helpful in his search for enlightenment.

The eight divisions

The eight stages are not to be taken in order, but rather support and reinforce each other:

- Right Understanding – Sammā ditthi

- Accepting Buddhist teachings. (The Buddha never intended his followers to believe his teachings blindly, but to practise them and judge for themselves whether they were true.)

- Right Intention – Sammā san̄kappa

- A commitment to cultivate the right attitudes.

- Right Speech – Sammā vācā

- Speaking truthfully, avoiding slander, gossip and abusive speech.

- Right Action – Sammā kammanta

- Behaving peacefully and harmoniously; refraining from stealing, killing and overindulgence in sensual pleasure.

- Right Livelihood – Sammā ājīva

- Avoiding making a living in ways that cause harm, such as exploiting people or killing animals, or trading in intoxicants or weapons.

- Right Effort – Sammā vāyāma

- Cultivating positive states of mind; freeing oneself from evil and unwholesome states and preventing them arising in future.

- Right Mindfulness – Sammā sati

- Developing awareness of the body, sensations, feelings and states of mind.

- Right Concentration – Sammā samādhi