Alternative religious movements are strange things – first of all, all emergent religions start out as just that: historical perspective would suggest, for example, that Judaism began as a variant on indigenous Canaanite faith systems that developed more and more divergent characteristics over time — though the opening lines of the Tanakh about the Creation of the world still echoes the Sumerian epic Enuma Elish depiction of creation (day by day order of creations of the former follows the succession of generations of Gods controlling that arose, governing those same creations – night and day, dry land and sea, etc. And the same can be seen in the beginnings of veneration of the Christ figure, the Buddha, Ras Tafari, etc.

BEYOND THAT… there’s the relationship of such movements to mainstream culture, and to one another. And perhaps most pertinently, the infrastructures and internal cultures that develop within them. They can lead to grand works of philanthropy, charity, personal liberation and also ruthless drives to acquire earthly power. To believe that any young religion isn’t equally capable of either might be considered naive in the extreme. So contemplation thereof can be instructive and cautionary.

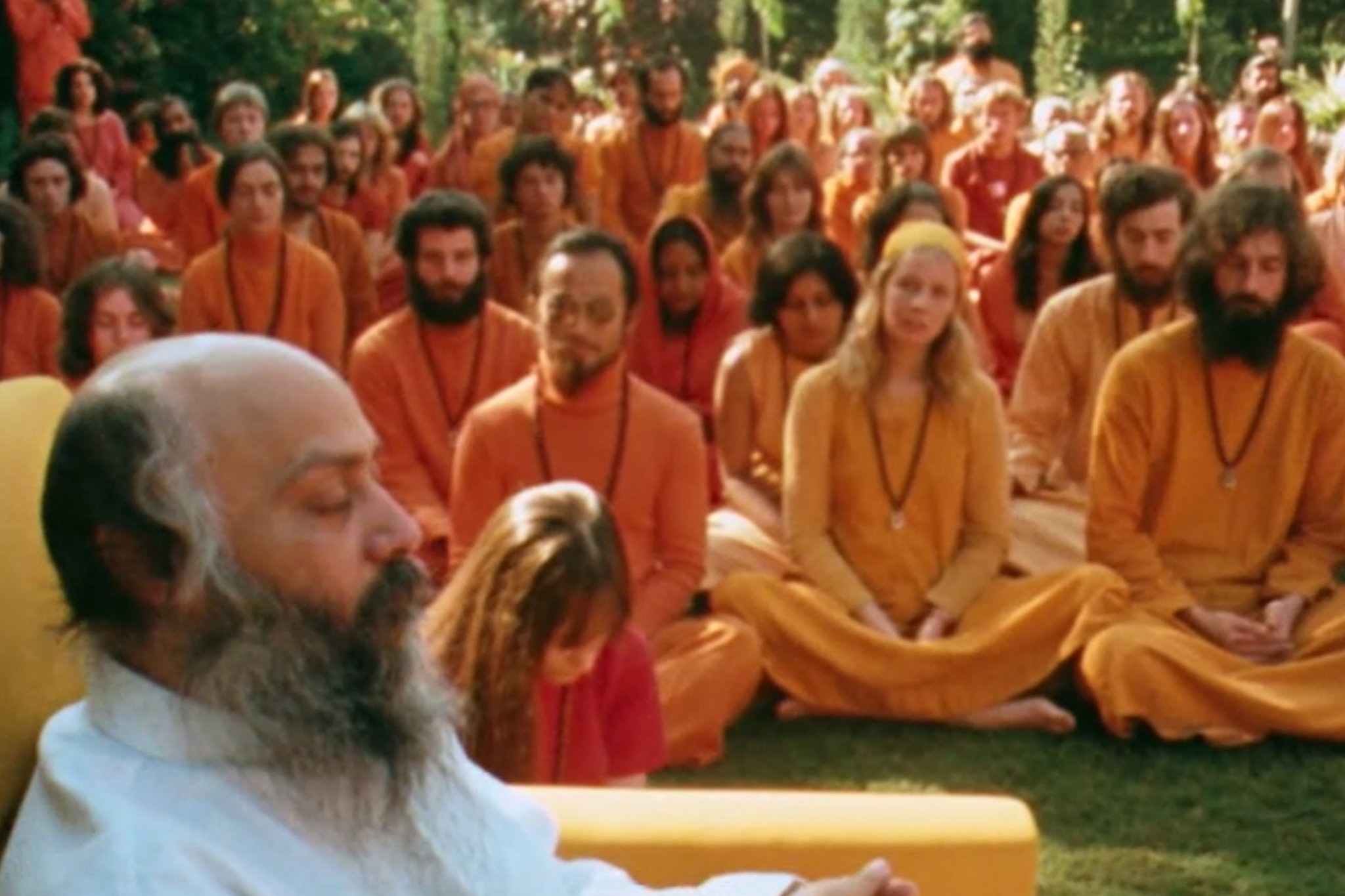

Ergo, the documentary Wild Wild Country regarding the followers of Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh bears watching and contemplation, perhaps. Here’s what the NY Times had to say about it:

“Jane Stork and Ma Anand Sheela, onscreen throughout the six-hour documentary series “Wild Wild Country” on Netflix, look and sound like friends of your grandmother who have dropped by to reminisce about the good old days.

“They don’t look like leaders of an international religious movement known for Rolls-Royces and ecstatic group sex, or women who went on the lam to Europe before serving time for crimes that include arson, wiretapping and attempted murder. It’s particularly jarring when the petite, gray-haired Ms. Stork acknowledges that she volunteered to carry out assassinations — twice — while serving the spiritual leader known as Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh. But that’s what their good old days entailed.

“Interviews with the two women, now in their late 60s, and with Prem Niren, another former Rajneeshee leader, form the backbone of “Wild Wild Country.” It’s a history of the tumultuous years in the early 1980s when the Bhagwan’s followers bought a 63,000-acre ranch in the high desert of Oregon, built an expansive commune called Rajneeshpuram and went to war with the locals, first in the nearby town of Antelope and then with the entire state.”

Keep in mind that a documentary, for all its pretext of objectivity, presents a selection of available material filtered by particular individuals’ perspective and likewise the narrative line they assemble from an infinite welter of information. So go into this knowing you’ll have to chew this seitan some if its to offer intellectual nutrition.