If you’ve read this blog before, you’ve heard me hold forth about the influence of American utopian societies on the international occult revival of the 19th and 20th centuries. Occult pioneers like Pascal Beverly Randolph and Ida Craddock were part of such societies and the body of thought called “New Thought” does jibe with a lot of modern occult technology. I noted a couple recent articles appearing on the Shakers, best known for their embrace of celibacy and the striking furniture they created. These articles all note that there are two Shakers left alive (replenishing the ranks of a celibate community is not the easiest trick to pull off). The New Yorker recently ran a piece on an exhibit of the little known art of Shaker “Gift Drawings,” apparently depictions of gnostic experience. The article begins:

The Shakers came to America two hundred and fifty years ago. Their founding leader, an Englishwoman named Ann Lee, preached Quaker ideals, like pacifism and gender equality, but added collective ownership, a work ethic to embarrass Balzac, and, trickiest of all for a utopia trying to grow, celibacy. Shaker missionaries recruited eloquently, and by the middle of the nineteenth century thousands of believers lived in villages as far south as Florida. Today, the religion has a grand total of two members—not that expansion is the only measure of success. No society chooses its legacy, and the fact that “Shaker” never became a slur like “Puritan” or a punch line like “Amish” has a lot to do with the slender, unembellished loveliness of their furniture. Shaker chairs are among the few art works that I would describe as tenderly severe. Looking at one hurts my back and soothes every other part of me.

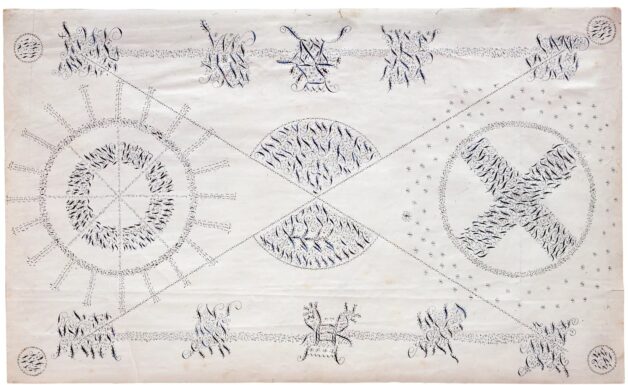

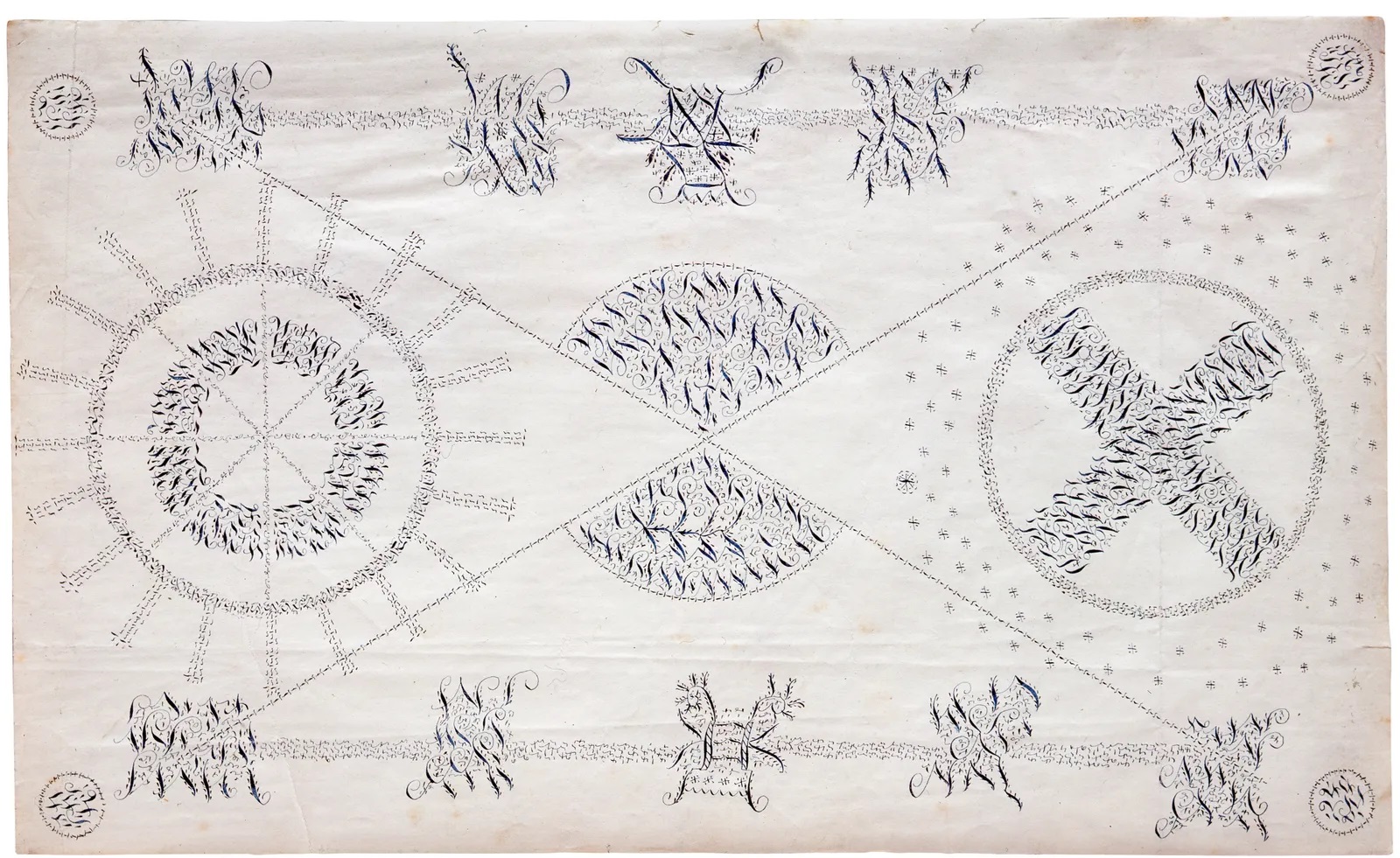

But this show is not about chairs, except for a single introductory piece. It is about watercolor, and ink, and paper, and how a group can embrace the visual with a bottomless appetite and somehow be world-famous for simplicity. To describe one work as Sister Polly Jane Reed’s drawing of the house of Holy Mother Wisdom, a Shaker spiritual entity, would not be incorrect. You should know, however, that there is a large blue eye staring out from the roof, and a tree growing there, and a compact cosmos of rainbow shapes surrounding the house, including a squelchy-looking thing that resembles a sea anemone but is really, per Reed’s tireless labelling, the trumpet of wisdom. Those labels! They pant after the pictures, sometimes explaining what’s what but always ornamenting with little confetti bursts of letters. Passing that chair on your way out, you may feel that the Shakers were abstemious in so many respects because they were already blazed on divinity. Furniture doesn’t need to be comfortable when everybody is too ecstatic to sit.

The organizers have put together a small but expansive display of small, expansive work. There are only twenty-one Shaker gift drawings on view, all borrowed from the same collection, in Massachusetts, but there are only about two hundred known gift drawings in existence. Most were made by mid-nineteenth-century women who reported visions of the spirit realm. Drawings were not owned by their makers but passed on from spirit to individual or, sometimes, to community. Visionaries were called “instruments,” not artists.

Read the entire article:

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2024/10/14/anything-but-simple-art-review.